“what am I missing; I keep relapsing and don’t know why I have such a difficult time remaining clean and sober?”

“what am I missing; I keep relapsing and don’t know why I have such a difficult time remaining clean and sober?”

How we treat addiction in treatment must change. The idea that we can provide information and teach an individual how to remain clean and sober is a fallacy. Most addicts and alcoholics are above average in intelligence and the question is “Don’t you think if they could be taught how to stop destroying their life they would merely read a book and the problem would be eliminated?” The answer is “Of Course.” Who would choose to drink, drug, or addictively act out knowing their life is over if they do?” Nobody. Thus, people know and they still partake in these behaviors.

Therefore, the answer is not merely education.

Facts:

- 9% of the U.S. population meets the criteria for substance use disorder (SUDs) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010);

- Drug-related suicide attempts increased by 41% from 2004-2011 (Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN);

- Therapeutic alliance is one of the greatest predictors of positive treatment outcomes (Straussner, 2012).

“Until an addict or alcoholic develops the capacity to establish mutually satisfying relationships, they will remain vulnerable to relapse and the continual substitution of one addiction for another (Phillip Flores)

What is Attachment Theory?

“Most of the psychopathology seen in the alcoholic is the result, not the cause of alcohol abuse.” (Valiant, 1983).

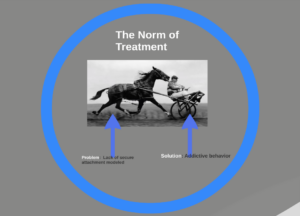

If we don’t begin treating the problem, which quite possibly stems from a lack of secure attachment modeled during childhood, as opposed to the solution, addictive behavior, we can count on continued treatment failure, often called resistance to treatment. Resistance to treatment seems to be a way of saying it’s the patient’s fault not ours. Therefore, we put the cart before the horse.

The result of putting the cart before the horse is the following:

- We admit a patient to treatment with distorted definitions of concepts learned as a child, i.e., honesty, hope, faith, courage, integrity, willingness, humility, brotherly love, discipline, perseverance, awareness, service

- The patient learned these definitions from their caregiver or parent from the models presented to them as children.

- How would the patient know these definitions are potentially dysfunctional if it is all they know?

- How effective will step work be if the patient doesn’t have a model or healthy definition of what the principles of the steps espouse?

Attachment theory assumes that the experience of childhood relationships shapes adult attachment styles. These experiences create the road map or internal working model for how the individual will perceive himself and others relationally (Bowlby, 1973).

The basic premise is that we only know what we know. For example, two men are sitting in the park discussing zoo animals. The one man asks the other if he has ever seen an elephant, to which the other man replies ‘no, what does it look like?’ The man states, ‘it is a large grey animal that has four hoofs, rough skin, floppy ears and trunk in the front’. The other man states ‘you mean like the tree trunk outside?’ The man replies ‘no, not a tree trunk’. To which many asks ‘You mean like the trunk of my car?’ The point is that the man will only know what an elephant looks like if he sees a picture or goes to the zoo. Similarly, if a child grows up with caregivers who are physically present although not emotionally present, thus, lacking a functional definition of emotional availability and intimacy, the child is more likely to have a stunted view of being emotionally present for others in their life. It is very possible that when this child becomes an adult, their innate need for secure attachment will not be met unless they see a model of what healthy attachment looks like.

The basic principle of Attachment Theory is that those with secure attachment (stronger emotional relationship with caregiver) are better able to regulate emotions and have fewer relationship problems. However, disruptions in the attachment system (insecure attachment) can lead to vulnerabilities in the sense of self and others as well as relationship problems; thus, leading to shame, co-dependency, and a need to numb pain via addictive behavior. Therefore, if we don’t address and model secure attachments to patients, they will stay stuck in the solution of continuously seeking to avoid and discharge pain through addictiveness.

Research suggests that relationships influence brain development and “relationships have the capacity to rebuild certain parts of the brain that influence social and emotional lives; clinicians can help clients to alter their attachment patterns with a secure clinical relationship. (Miehls, 2011, p. 82).

The bottom line in defining Attachment Theory is that the goal of treatment needs to be focused on changing the definition and model of what it means to feel included, loved, and secure. “The inability to establish healthy relationships is a major contributing factor to relapses and the return to substance use.” (Flores, 2004). Thus, the answer to “sh*t what am I missing?” is: Not having had a clear model of secure attachment because it was partially or completely missed during childhood. As Flores stated:

“Therapists must be able to challenge, soothe, care, love, and if necessary, fight with a patient if they are able to provide a full range of emotional experiences that can potentially come alive in an authentic relationship. (Flores, 2004, p. 259).

To sum up part one of this article, unless we provide a solid definition of concepts that we see as normal (based on definitions that were modeled) albeit dysfunctional and damaging, the way we work the 12 steps will be flawed and based on dysfunctional definitions, lacking much change in behavior. Alternatively, we can utilize the 12 steps as a corrective experience by interpreting each step as follows:

Interpreting the 12 Steps from an attachment perspective:

Step 1: The experience of abandonment;

Step 2: Permission to hope; integration to others;

Step 3: Taking a risk (vulnerability) to attach

Step 4: Taking a risk to attune with self

Step 5: Taking a risk to attach to another person

Step 6-7: Correcting and repairing relationship with self

Step 8-9: Correcting and repairing relationships with others

Step 10: Personal responsibility for securely attached relationships in my life

Step 11: Solidifying a secure attachment to my Higher Power

Step 12: Increasing my ability to model securely attached relationships to others

The preceding article was solely written by the author named above. Any views and opinions expressed are not necessarily shared by GoodTherapy.org. Questions or concerns about the preceding article can be directed to the author or posted as a comment below.

Please fill out all required fields to submit your message.

Invalid Email Address.

Please confirm that you are human.

Leave a Comment

By commenting you acknowledge acceptance of GoodTherapy.org's Terms and Conditions of Use.