Sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on a person’s sex. Anything from demeaning comments and gestures to denying access to equal opportunities based on sex may be considered sexist, as well as treating someone as less competent because of his or her sex, whether in the workplace or classroom, on the streets, or at home. Typically, sexist remarks, behavior, and perspectives are thought of as being targeted at women, who are largely afforded less privilege than men.

Ambivalent Sexism: An Important Distinction

The theoretical concept of ambivalent sexism, established by social psychologists Dr. Peter Glick and Dr. Susan Fiske, distinguishes between two main types of sexism toward women:

The theoretical concept of ambivalent sexism, established by social psychologists Dr. Peter Glick and Dr. Susan Fiske, distinguishes between two main types of sexism toward women:

- Hostile sexism refers to the more common and easily recognizable sexist expressions that reflect an attitude of condescension toward women. For instance, any words, actions, or attitudes that support the notion that women are incompetent and inferior to men are reflective of hostile sexism.

- Benevolent sexism, described by Glick and Fiske (2001) as “a subjectively favorable, chivalrous ideology,” is a bit harder to pinpoint, as it encompasses the nonaggressive mindset that women are inherently more fragile, delicate, and sensitive than men, and therefore less capable of or suited to performing certain tasks than their male counterparts. An example of this is the belief that women are not strong enough to lift heavy boxes and operate heavy machinery, when, in fact, there are plenty of women who possess the strength and competence to do such things.

Gender Roles and Stereotypes

Gender roles are cultural constructs that dictate how each gender ought to behave. For example, though somewhat less common today, girls are expected to play with dolls and boys with trucks. Because culture is the culprit, gender roles may shift over time in the same way cultural norms do. For example, according to a 1996 study, only one in five Americans in 1938 accepted the idea of a married woman with a job, compared to four out five Americans in 1996.

Gender stereotypes on the other hand, have less to do with how one ought to behave and more to do with beliefs about how men and women do behave. Many studies show that gender stereotypes are pervasive and both men and women are guilty of them. A 1981 survey study by researchers Mary Jackman and Mary Senter discovered that the majority of both male and female survey respondents believed women to be more emotional than men. Nearly 75% of all participants stereotyped men and women in the same way, regardless of their own gender.

Although gender stereotypes are usually based in some version of truth or experience, that does not make them accurate. Additionally, though gender stereotypes are not necessarily prejudice, they can lead to problematic attitudes towards a certain gender and contribute to sexist beliefs.

Objectification as a Form of Sexism

Sexual objectification is sometimes considered a form of sexism, as it reduces a person to a source of sexual appeal and gratification and disregards their intellect, emotions, and character traits. Some would argue that pornography and prostitution promote sexism and reinforce gender stereotypes as they depict people as mere sexual objects.

Sexism in Psychotherapy

Unfortunately, sexism can arise in many different life situations. In some cases, sexism can occur during therapy.

Awareness of sexism in psychotherapy practices emerged in the 1970s, sparked primarily by a well-known study conducted by the Brovermans et al. (Broverman, Broverman, Clarkson, Rosenkrantz, and Vogel, 1970). The study examined biases shared among therapists that men were more psychologically healthy than women. While it is true that women have consistently been more likely to seek out psychotherapy than men, this does not necessarily mean they are somehow more apt to be mentally and emotionally flawed. And yet, this glaringly sexist perspective is still held by some to this day.

Others simply acknowledge that based on presumed gender roles such as the strong, emotionally-resilient man and the soft, sensitive female, many men feel embarrassed to seek therapeutic assistance (Winerman, 2005). Therefore, women must contend with the sexist notion that their desire for therapeutic support reinforces the idea that they are, in fact, the weaker sex; and men must grapple with the societal stigma that to ask for help in any form is a shame-inducing sign of weakness.

Historically, women are the ones who have endured the bulk of sex-based stigmatizing in psychotherapy. One of the earliest arguments made by feminists, especially when debate first sparked in the 1970s, is that traditional therapy practices treated women unfairly by objectifying and sexualizing them as well as imposing feelings of guilt and shame on them for not meeting society’s heavily stereotyped expectations and allowances for what a woman is capable of being and achieving (Mowbray, 1995). For example, if a married woman was experiencing distress due to her desire to have more personal freedom and independence, her therapist—almost certainly a male in the early days of psychotherapy—would be likely to gear counseling sessions toward encouraging her to view her freedom-seeking urges as flawed and instead recommend she focus on accepting and embracing her subordinate wifely duties. As a result, many women who sought therapy due to personal unhappiness were made to feel even worse about themselves and their longings.

To reduce sexism in therapy, organizations such as the American Psychological Association, the National Coalition for Women’s Mental Health, the National Organization for Women, and others established “nonsexist therapy” guidelines in the 1970s and 1980s (Mowbray, 1995). In the years since, others have followed suit, and most people now recognize and refrain from engaging in more obvious forms of sexism in treatment; however, in spite of increased regulations and awareness, sexism may still appear in therapy.

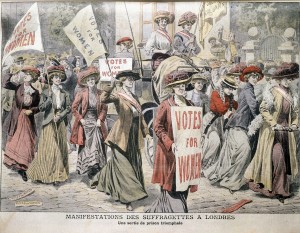

History of Sexism in America: The Fight for Equal Rights

Throughout American history, the prevalence of sexism was most evident in the ways early American society enforced the roles and rights of women. Women were thought incapable of holding positions of power and belief in their inferiority permeated both government and society. Throughout the decades, many people spoke out against the oppression and fought for equal rights.

By the mid-1800s, the women’s rights movement finally gained traction and the first assembly devoted to women’s rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, was held in 1848. This assembly marked the beginning of the women’s suffrage movement. The fight for equality continued and several key figures and events contributed to the forward progress of the women’s rights movement:

- 1869: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony created the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and Lucy Stone, a women’s rights lobbyist, formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

- 1890: The NWSA and AWSA united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This unity gave the suffrage movement the momentum it needed to focus efforts on gaining the right to vote.

- 1913: Alice Paul formed the National Woman’s Party, which utilized more militant strategies of picketing, organized rallies, and marches.

- 1916: Jeannette Rankin was the first woman elected to Congress.

- 1920: The 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution became law, giving women the right to vote.

- 1961: Eleanor Roosevelt was appointed head of President Kennedy’s Commission on the Status of Women. The Commission made recommendations on how to decrease discrimination in the workplace.

- 1962: Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, which re-energized the women’s rights movement.

- 1972: Title IX of the Educational Amendments prohibited sex discrimination in educational environments. Afterward, enrollment of women in athletic programs and schools increased.

- 1973: United States Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade granted women the right to choose to have an abortion.

- 2009: Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act relaxed the statute of limitations on workers’ rights to sue for pay discrimination.

Though the fight for equality has made great strides in abolishing many negative effects of sexism, pay gaps, health care problems, and persistent underrepresentation in government are among many issues still perpetuated by sexism.

Sexism in the Workplace

Occupational sexism is discrimination that involves treating someone less favorably than another based solely on his or her sex, or on his or her sexual orientation, in the workplace. This may involve overtly sexist words and behaviors, or it may also refer to the experience of being qualified for a job but not getting it based on gender.

To describe the unseen barriers that women, in particular, tend to run into as they climb the so-called corporate ladder, the term “glass ceiling” is often used. Since its first documented usage in a 1986 article in the Wall Street Journal, the concept has grown into The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission, established as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1991. The commission focuses its work on better understanding and ultimately removing the barriers, policies, and perceptions that hinder career advancement for women and minority groups.

As the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) states on their website, “The law forbids [sex-based] discrimination when it comes to any aspect of employment, including hiring, firing, pay, job assignments, promotions, layoff, training, fringe benefits, and any other term or condition of employment.”

There are a number of specific laws currently in place to protect the rights of those who fall prey to instances of occupational sexism. The following are gender-based laws enforced by the EEOC:

- The Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which protects women from discrimination based on “pregnancy, childbirth, or a medical condition related to pregnancy or childbirth.”

- The Equal Pay Act of 1963 (EPA), which states that it is illegal to pay unequal wages to men and women “if they perform equal work in the same workplace.”

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII), which states that it is illegal to discriminate against an individual on the basis of “race, color, religion, national origin, or sex.”

These laws also protect anyone who decides to report a violation. If a person feels he or she has been discriminated against in the workplace based on sex or gender identity, the EEOC requires that a “charge of discrimination” be filed within 180 calendar days from when the incident took place. Employees and job applicants of federal organizations, however, must file within 45 days. The filing of the charge must be done at the EEOC office nearest to where the act of discrimination took place. The EEOC also offers an online assessment tool at www.eeoc.gov to determine whether an experience qualifies as sex-based determination.

Sexism and Mental Health

When it comes to mental health issues, some gender inequalities exist among various diagnoses. Women are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and somatic complaints, and they are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression. An article on gender and women’s mental health from the World Health Organization suggests that because one’s gender affects the power one has over many factors that impact mental health, women may be more susceptible to certain mental health issues.

Gender-specific risk factors for anxiety and depression overrepresented among women include gender-based violence, socioeconomic barriers, income inequality, lower social status, and a perpetual role as caretaker. Additionally, thanks to gender bias among many health care professionals, women are far more likely than men to go home with a diagnosis of depression even when similar assessment scores are present.

Although these problems exist, there are ways to prevent the impact of sexism on mental health. According to the World Health Organization, there are three factors that can shield a person from mental health problems. These include:

- A sense of independence that allows one to experience control when faced with traumatic event.

- Access to resources that empower and strengthen one’s ability to cope and survive.

- Psychological caring and guidance from family, friends, and mental health care providers.

Example of a Sexist Stereotype: The Female Driver

A common example of sexism in popular culture is the stereotype that women drivers are more dangerous than male drivers. This view has been around for years, depicted in everything from magazine ads to YouTube videos, and it appears to be shared cross-culturally.

For example, in late 2013, Beijing police officers were cited as making critical, condescending comments toward female drivers. According to the report, suggestions were posted on the police department’s official microblog, saying things like, “Some women drivers lack a sense of direction, and while driving a car, they often hesitate and are indecisive about which road they should take. . . . [W]hen they’re driving by themselves, they’re not able to find the way to their destination, even if they’ve been there many times.” There was a backlash from Chinese Internet users, who also posted on the police department’s microblog, expressing the widely shared sentiment that the officers’ comments were sexually discriminatory (Agence France Presse, 2013).

Combating Negative Stereotypes and Reducing Sexism

Negative stereotypes and sexism affect communities in profound ways. Both have a detrimental effect on the economy, progression, and mental health within workplaces, schools, and other institutions. Fortunately, we can all foster positive change within our social circles and help tear down some of the barriers sexism and stereotypes create for individuals. Here are three simple ways to combat sexism and negative stereotypes where you live, work, and play:

- Speak up. If you hear someone saying things like, “Women are terrible drivers,” or “Stop crying. Boys are supposed to be tough,” inform him or her that such statements perpetuate sexism and harmful stereotypes that affect millions of people. Do not remain silent or play along. People are not always aware that their words may be damaging to other people, and increasing their consciousness around issues like sexism helps promote the small changes that often add up in big ways.

- Talk to your children. Many of our behaviors as adults are rooted in childhood experiences. Unfortunately when it comes to sexism and negative stereotypes, many children are never taught why these are harmful and many parents are directly complicit in perpetuating them by making seemingly harmless statements their children overhear and grow up repeating. Take a moment, sit your little ones down, and explain to them why it’s harmful to make fun of girls or boys because of the way they are born. Teaching your children about the dangers of sexism and stereotypes is a great way to affect change in the next generation of policymakers, thought leaders, and citizens.

- Educate yourself. No matter how noble your intentions are, or how conscious you think you are of sexism and/or stereotypes, chances are you have engaged at least once in an example of everyday sexism or stereotyping. Take a moment and read, watch a video online, or listen to a podcast about different forms of discrimination such as microaggressions to better understand the seemingly innocuous ways we sometimes engage in them.

References:

- Agence France Presse. (2013, October 30). Beijing police offer women drivers offensive advice, appropriate backlash ensues.Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/10/30/beijing-police-women-drivers_n_4176282.html

- Broverman, I., Broverman, D., Clarkson, F., Rosenkrantz, P., and Vogel, S. (1970). Sex role stereotypes and clinical judgements of mental health. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24, 1–7.

- Corey, G. (2009). Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Executive summary: Fact Finding Report of the Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/reich/reports/ceiling1.pdf

- Gender and women’s mental health. (n.d.). In World Health Organization. Retrieved January 23, 2015, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

- Glick, P., and Fiske, S. (2001, February). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, Vol. 56, No. 2, 109–118. Retrieved from http://cocomaan.net/00000487-200102000-00001.pdf

- Milestone in U.S. women’s history. (n.d.). In IIP Digital US Department of State. Retrieved January 23, 2015, from http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2012/03/201203091900.html#axzz3Pew4Ic5V

- Mowbray, C. T. (1995). Nonsexist therapy: Is it? Women & Therapy, 16.4 (9).

S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Sex-based discrimination. Retrieved from http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sex.cfm - Myers, D. G. (1999). Social Psychology (6th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw Hill Companies.

- The 1960s-70s American Feminist Movement: breaking down the barriers for women. (n.d.). In Tavaana. Retrieved January 23, 2015, from https://tavaana.org/en/content/1960s-70s-american-feminist-movement-breaking-down-barriers-women

- The Women’s Rights Movement, 1848–1920. (n.d.). In History, Art & Archives United States House of Representatives. Retrieved January 23, 2015, from http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Essays/No-Lady/Womens-Rights/

- S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Sex-based discrimination. Retrieved from http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sex.cfm

- Winerman, L. (2005, June). Helping men to help themselves. Monitor on Psychology, Vol. 36, No. 6, 57. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/jun05/helping.aspx

- Women’s Rights Timeline. (n.d.). In Annenberg Classroom. Retrieved January 23, 2015, from http://www.annenbergclassroom.org/Files/Documents/Timelines/WomensRightstimeline.pdf

Last Updated: 08-25-2015

- 4 comments

- Leave a Comment

Emily

August 4th, 2017 at 8:17 AMIn my experience, therapists (male and some females) almost always trivialize and pathologize the pain a woman experiences after male violence (domestic violence and sexual violence). I volunteer and work with abused women and every time they contact the shelters or hospitals, they are directed to a counselor or psychiatrist who promptly diagnoses them, and the diagnosis is usually: “Borderline Personality Disorder”. Then, when it comes time for the victims to take their abusers to court, the abuser’s defense uses the woman’s new diagnosis to discredit her. In addition to this vicious cycle, these women–who are experiencing legitimate, normal emotional and psychological pain–are given tons of mind-numbing psychiatric medication which destroys their bodies and spirit–and tells them that the pain and indignation they have from male violence is flawed or wrong, as in–“you’re mentally ill for speaking up and crying about being abused”. Some women, who seek a medical services after rape, are committed against their will to an inpatient ward–where they are treated as a violent threat, denied basic toiletries and “must comply” in order to be released–all after being raped.

And whenever I try to raise concern about this pattern I’ve noticed in my community I am immediately dismissed with the following excuses:

“It’s just a few bad apples”

“That’s just your interpretation”

“Well, you don’t know the circumstances…”

“We have to keep people safe…”

“We’re not perfect…”

To that I say, no–nobody’s perfect. But carrying out psychiatric abuse on abused women is far from just “not perfect”; it’s blatant and unnecessary sexism. I am also disgusted by the constant dismissal of sexism towards women from mental health professionals; it seems like therapists just want a pat on the back for “not being as sexist as we were in the 1960s…” and it doesn’t matter how real-female-clients are being treated NOW.Beth

July 2nd, 2018 at 4:17 PMYou just described me. I keep seeking help and I can’t find a therapist to listen to me long enough to realize I wasn’t born this way. My psychiatrist (a woman) talked with me for 30 minutes and gave me a Borderline Personality diagnosis and a bagful of meds, and said, “Call me when you need a refill.” I don’t know what to do anymore.

Camryn

May 15th, 2018 at 8:32 AMsexism is stupid and wrong. It should stop right now. BOOOOOO sexism.

Leave a Comment

By commenting you acknowledge acceptance of GoodTherapy.org's Terms and Conditions of Use.