What am I missing? Part 2: Applying Attachment Theory to Treatment and Recovery

Part I of this article provided a definition and basic framework for Attachment Theory. Attachment theory provides that most individuals did not grow up with a model for secure attachment; thus, treatment for addiction requires providing a model of secure attachment so that individuals can practice healthy behavior in response to pain and discomfort other than acting out in addictive behavior.

Theoretically, Mary Ainsworth PhD (1969) defined secure attachment as developing when a caretaker shows awareness of a child’s emotions and quickly attends to the child when distressed. The child’s perception is that the caretaker is consistent in presence and provision; thus, the child feels safe in exploring their world because of their sense of certainty that their caretakers will be there for them in a nurturing manner if needed. Overall, attachment theory assumes that the experiences of childhood relationships shape adult attachment style; thus, for example, the reason why adults who were physically abused as children have a high propensity for abusing their children. This is the behavior that was modeled and typically the only mode that the adult has for responding to anger.

The Scientific Link Between Attachment and Addiction:

Attachment theory posits that an infant learns necessary skills for survival and the development of an Internal Working Model (IWM) whereby the definition of how the person views the world, themselves, and others is defined. “Attachment representations show predictive associations with a wide range of pathological behavior including personality disorder(s), mood disturbance, [substance dependence] and psychopathology” (Caspers, Yucuis, Troutman, & Spinks, 2006). Therefore, the authors conclude that childhood attachment styles (secure or insecure) have a direct impact on the prevalence of Substance Abuse Disorders.

Researchers Kendler and Prescott (2006) reviewed the findings of the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development (VTS) for the purpose of exploring the depth of influence between genetics and environment as it relates to addictiveness and mental health disorders. VTS had a sample size of 2,762 white twins between the age of 8-16 years old and their families. Kendler and Prescott concluded that there are no genes specifically responsible for Substance Use Disorder, but rather, there are genes that an individual can inherit that predispose them to patterns of behavior closely associated with Substance Use Disorder. Additionally, the authors concluded that if children are brought up in “protective environments”, even though genetically they are predisposed to patterns associated with Substance Abuse Disorder, the environment has a likely potential to be a protective factor against Substance Abuse Disorder.

The Brain:

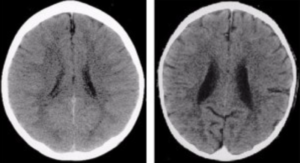

Finally, researchers have directly correlated neurobiology of the human brain and the importance of caregiver attachment relationships during childhood to mental health in adulthood (Miehls, 2011, p. 82). Additionally, the research has indicated that insecure attachments during childhood affects, negatively, the development of certain areas of the brain. Moreover, Miehls states “relationships have the capacity to rebuild certain parts of the brain that influence our social and emotional lives,”) (Miehls, p. 81).

The benefit of the connection between neurobiology and attachment is that brain neuroplasticity (the ability of the brain to be re-formed) allows for a corrective experience or secure attachment model during adulthood leading to positive changes in the patient; thus, lessening the need to utilize addictive behavior to deal with abandonment, trauma, abuse, and emotional pain etc. Moreover, the implication for treating substance dependence indicates the importance of a secure attachment relationship between the clinician and the patient to provide a baseline model or definition.

Addiction as an Attachment Disorder

The attachment system of a person is developed as a child in proportion to the relationship between the child and the caregiver; thus, if the attachment process is deficient, the child will have issues related to emotional regulation. Therefore, as an adult, the person is likely to utilize drugs and other substances to regulate emotions as a means of adapting to an inability to regulate emotions learned as a child (Kohut 1977).

Drugs create an ability for a person to have the illusion of self-esteem, self-confidence, worthiness and “increase feelings of being alive” (Kohut 1977). An addict attempts to define comfort and security (missing in their vocabulary) through the use of addictive substances or behavior; however, outside sources other than secure modeling will lead to continued dysfunctional definitions and continued addictiveness.

Treating Addictiveness and Substance Dependence through Attachment Theory:

Recent studies have positively confirmed that a direct link exists between insecure attachment and substance dependence (Schindler, Thomasius, Sack, Gemeinhardt, 2007; Schindler, Thomasius, Sack, Gemeinhardt & Eckeert, 2005).

“Attachment Oriented Therapy” (AOT) has been described as “a way of eliciting, integrating and modifying styles represented within a person’s internal working model” Flores (2004) p. 214). Flores (2001, 2004) goes on to explain that the IWM must be changed or addiction will continue or substitution of one addiction for another will persist. The key point is that when an individual begins to learn (which requires a model) how to self-soothe, thus, learning how to regulate emotions and feelings, they will avoid seeking outside sources as a means of managing these emotions (Blaine & Julius, 1977; Flores, 2001; Flores, 2004).

The vast majority of individuals in treatment today have been exposed, multiple times, to the treatment experience; Therefore, what is missing? Why the extreme difficulty in remaining sober? Haven’t they been taught well? Has the education system (the treatment industry) failed them? The answer is not black and white, but rather, exists within the statement: We must begin to treat patient’s differently. The idea that we are able to teach patient’s how to stay sober doesn’t equate to their ability to apply what they have learned or feel safe enough to explore the deeper problem of why they continue to utilize addictive behavior to escape emotional pain.

AOT is rooted in providing a “secure base” for an individual so that they may begin to explore themselves from the inside out. Attachment theory correctly posits that by providing a model in treatment of a safe, secure base, the patient will have the ability to cease seeking answers outside themselves (drugs, alcohol, sex, food etc.) and begin to heal from the inside out. Moreover, by providing this safety, patient’s have the ability to express and feel emotions in a vulnerable and authentic capacity; thus, the willingness to address the problem, rather than the solution (the addictive behavior).

“A Different Way to Treat People”

Conclusion

Overall, what is missing in treatment today is the understanding and compassion of being relational with patients. The irony in this statement is that AA promotes compassion and being relational with individuals; however, this is the part that most traditional treatment misses. Alternatively, traditional treatment provides an education as opposed to modeling behavior that provides the ability to develop secure attachment needed for change.

Unfortunately, most addicts (probably most human beings in general) have not had a model for secure attachments, thus, leading to substance abuse and addictive behavior as a means of avoiding emotional pain. For treatment and thereafter, AA and therapy to be effective, the following suggestions are necessary:

- Treatment must be focused on modeling secure attachment. This requires risk on the part of the treatment provider and a demonstration of self-disclosure and identification from the treatment team as opposed to a one-up position of authority;

- Development of trust and alliance with the patient is critical if the patient is going to address and change learned abusive and dysfunctional patterns during childhood; thus, leading to the need to utilize addictive behavior as a means of avoiding emotional pain;

- Continuation of care is critical. Thirty days in treatment merely scratches the surface. Without a long-term aftercare plan, i.e., Partial Hospitalization, Intensive Outpatient and therapy, that focuses on abuse, attachment, and secure attachments, we can expect relapse rates after inpatient treatment to remain near 5-7% within one year of inpatient treatment; and

- “A different way to treat people” must become the norm as opposed to the exception in treatment.

© Copyright 2007 - 2025 GoodTherapy.org. All rights reserved.

The preceding article was solely written by the author named above. Any views and opinions expressed are not necessarily shared by GoodTherapy.org.